The art of liquidation

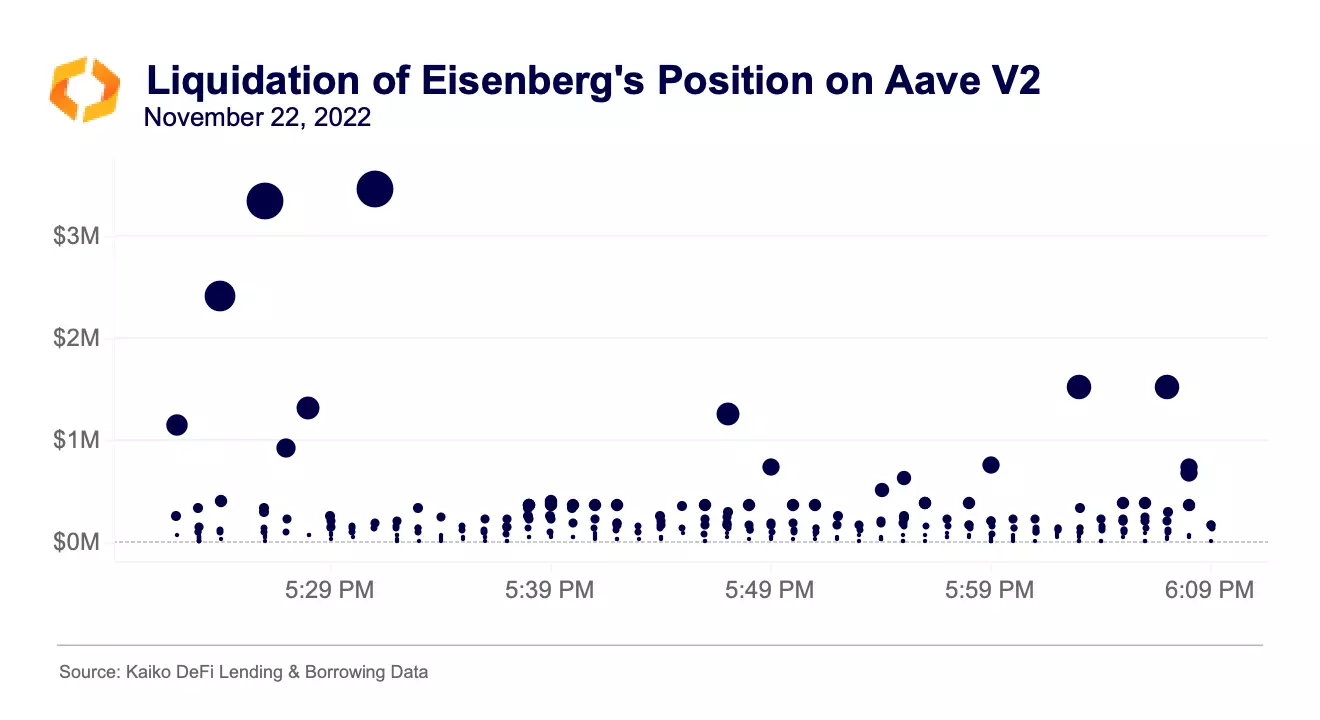

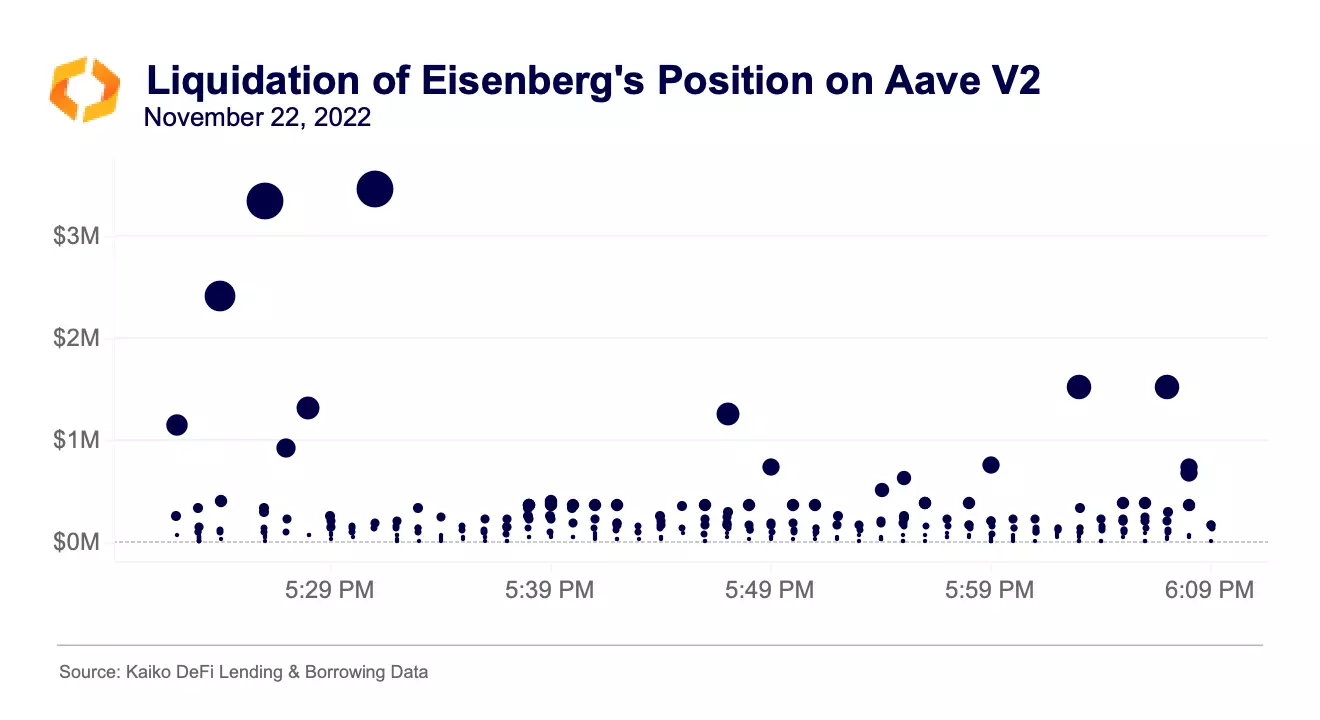

Liquidations on DeFi lending and borrowing protocols follow some basic principles: a liquidator sees that a position has entered the liquidation threshold, then the liquidator repays some amount of the borrowed token in exchange for a corresponding amount of the collateral at a discount, generally in the range of 4% to 10%. In the case of Avi Eisenberg’s attempted exploit, the collateral was USDC and CRV was borrowed, meaning liquidators repaid CRV to receive USDC at a discount.

However, like most things on-chain, liquidation is more complicated than it may seem. Continuing with the Eisenberg example, because the position was so large – about $40mn CRV borrowed – it was difficult for liquidators to source CRV tokens to repay the loan in an efficient manner.

As charted below, the liquidation of this position took about an hour and over 300 transactions, with 20 different liquidators joining in.

The price of CRV rose while the position was being liquidated, which created a mismatch between the (discounted) collateral and loan value, eventually saddling Aave with 2.6mn CRV tokens of bad debt.

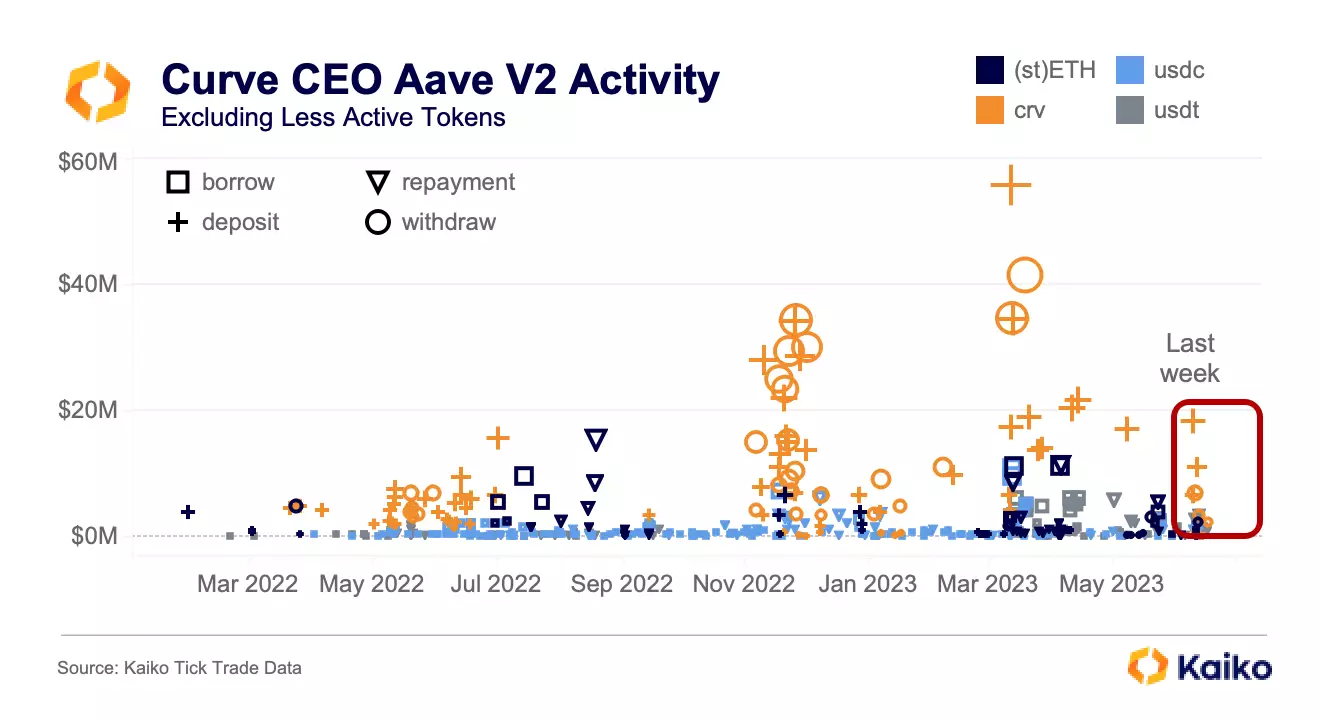

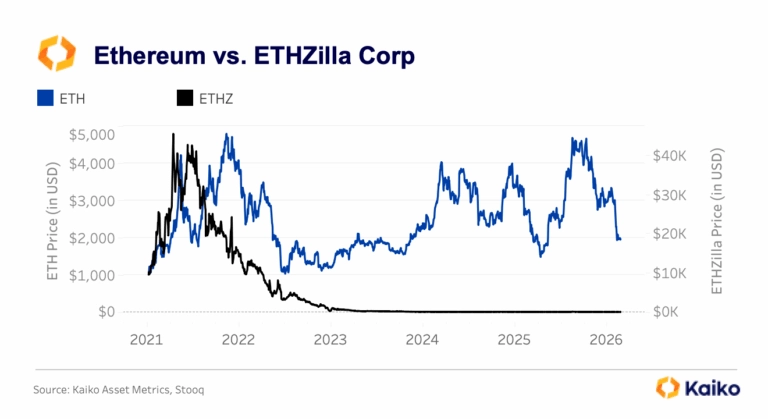

This is the opposite of how a hypothetical liquidation of Egorov’s position might go. In that instance, liquidators would repay the USDT loan and receive discounted CRV tokens. However, this position is significantly larger – the Aave V2 collateral represents about 30% of CRV’s circulating supply. When including other lending and borrowing protocols, this figure approaches 50%.

Again, liquidity comes into play, this time on the back end of the transaction. Liquidators will only repay a loan if it’s profitable for them to do so and are unlikely to hold onto CRV tokens, instead opting to sell them for a stablecoin or ETH. For example, in many of the liquidations shown above, liquidators were borrowing ETH from dYdX, swapping ETH for CRV, repaying CRV, receiving USDC, swapping for ETH, and keeping any extra ETH as profit – all in a single transaction.

In the case of Egorov’s position, liquidators would do something like: swap ETH for USDT, repay USDT, receive CRV, swap CRV for ETH. It’s only guaranteed to be profitable if they are able to immediately sell the CRV tokens they receive with decent execution. Additionally, selling pressure from the early liquidations would further drop CRV’s price, possibly to the point where the collateral is worth less than the borrowed tokens.

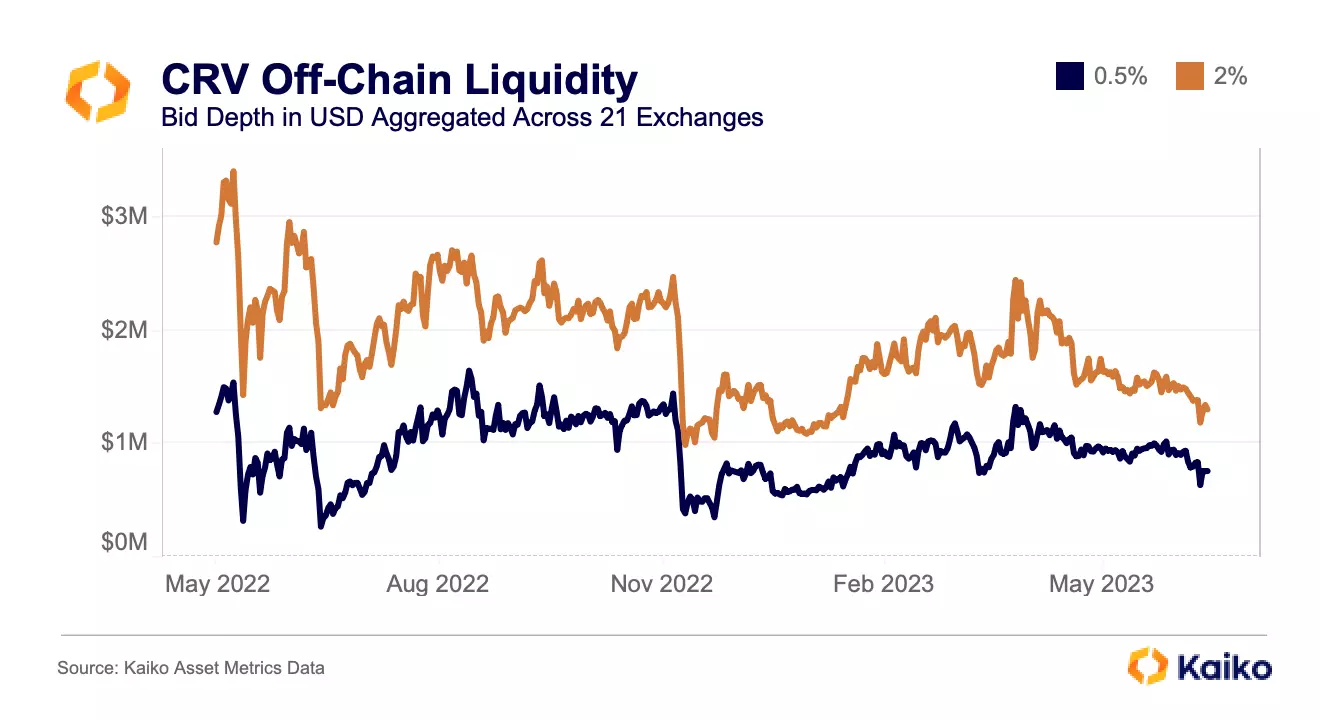

The single largest source of liquidity for CRV is on Curve itself in the CRV-ETH pool, which currently stands at about $50mn TVL. Uniswap V3, meanwhile, stands at just over $4.5mn across all of its CRV pools.

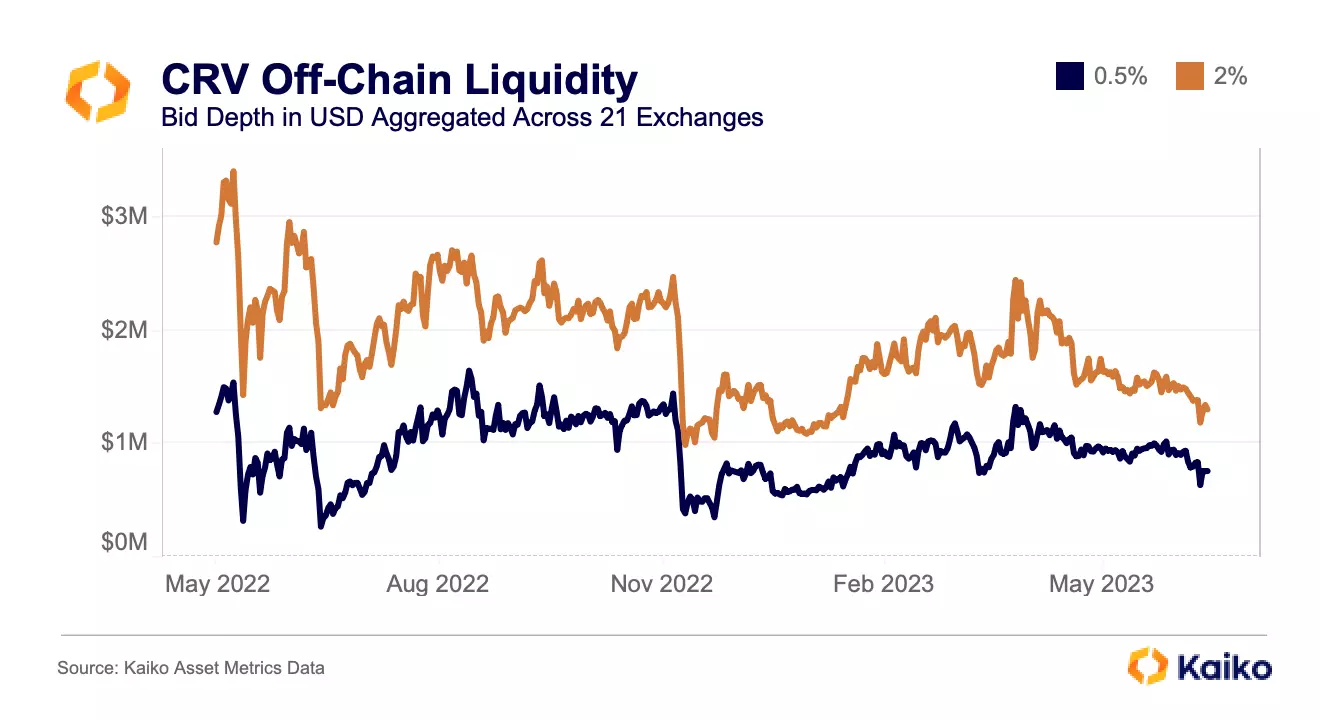

To make matters worse, centralized exchange liquidity is also thin, with just over $1mn worth of bids within 2% of the mid price, aggregated across all of the exchanges that we cover.

It’s safe to say that there is nowhere near enough liquidity to make liquidating the entire position profitable, which raises the specter of bad debt.

Bad debt

Eisenberg’s failed exploit of Aave that nonetheless left it with 2.6mn CRV tokens of bad debt, a small enough figure that governance opted to purchase using funds generated from its Collector Contract. However, if Egorov’s position were to be liquidated, it’s highly likely it would result in a much larger amount of bad debt. A hole of this size would likely require Aave to utilize its much-maligned (by me) Safety Module, which sells AAVE tokens to cover bad debt. I’ve already written a few times expressing my belief that the Safety Module is poorly designed and a significant risk to the AAVE token. Fortunately, governance discussions regarding diversifying the Safety Module are ongoing.

Conclusion

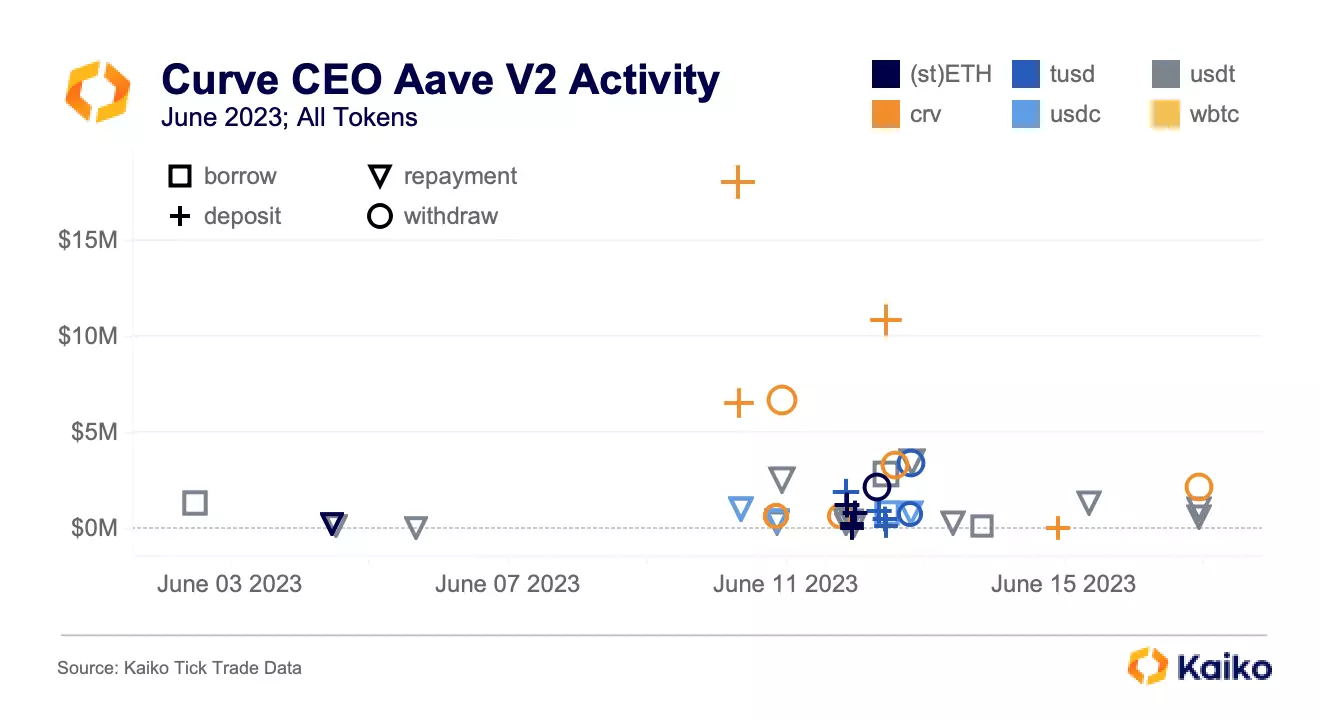

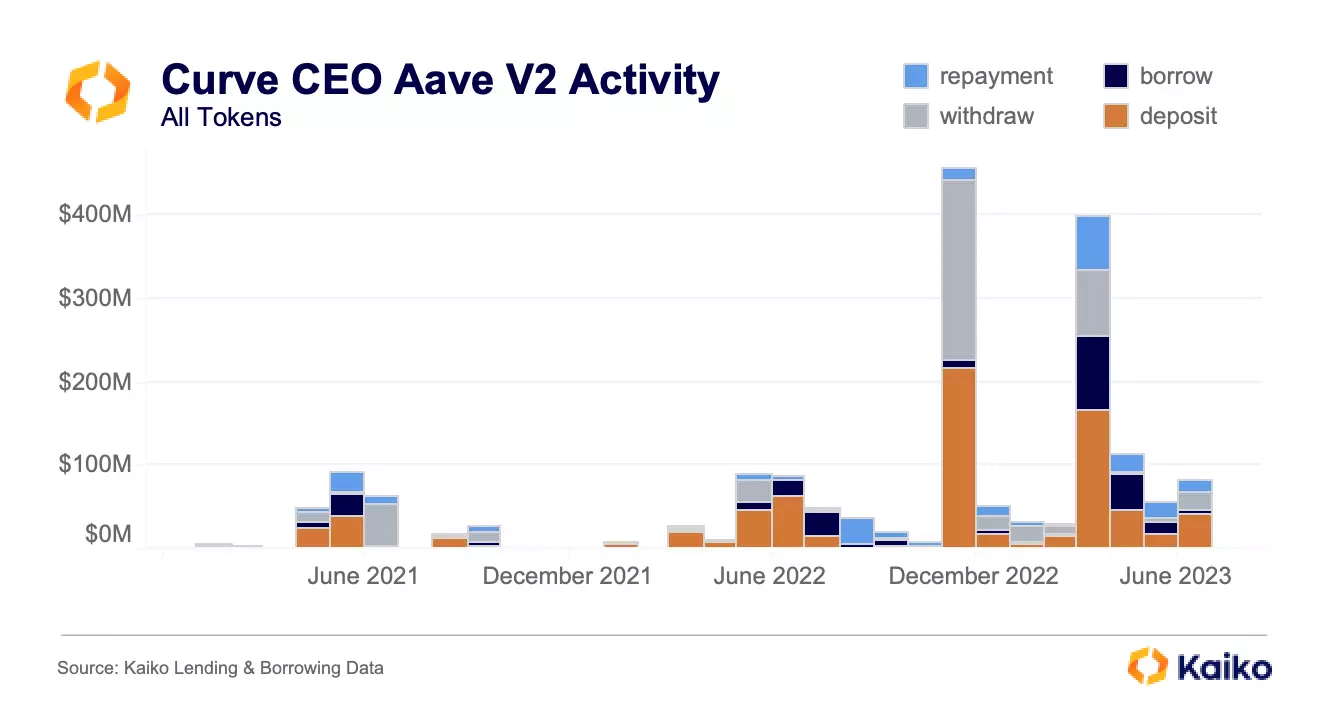

Like many things in crypto, there was a healthy dose of speculation last week when Twitter found out about this position. What if Egorov never intends to repay? What if he’s fine getting liquidated? If anything, the data suggests the reverse: he has diligently maintained the health of his loan even as its size has grown beyond what Aave governance is comfortable with.

With that said, it is concerning to see such a large portion of CRV’s circulating supply used as collateral, as crypto is certainly no stranger to flash crashes. Ultimately, this saga proves the importance – especially for lending and borrowing protocols – of monitoring the data and responding quickly as risks change.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()